Authors: Justice Annabelle Bennett AC SC, Justice Stephen Burley, Cynthia Cochrane SC, Andrew Fox SC, Julian Cooke SC, David Larish, Benjamin Mee, Robert Clark, Samuel Hallahan, Anna Spies, Angela McDonald, Edward Thompson, Joseph Elks, Anna Elizabeth, Sue Gilchrist, John Lee, Irini Lantis, Timothy Gollan and Byron Turner

The Australian patent system is governed by the Patents Act 1990 (Cth). The origins of that Act, and the Australian patent system generally, can be traced back to English law and the Statute of Monopolies 1623. 1

Section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies 1623 (which is expressly referred to in Section 18(1)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth)) provided an exception for patents to the general position that monopolies were contrary to law. Section 6 described the carve-out for patentable inventions in the following terms:

Provided alsoe That any Declaracion before mencioned shall not extend to any tres Patents and Graunt of Privilege for the tearme of fowerteene yeares or under, hereafter to be made of the sole working or makinge of any manner of new Manufactures within this Realme, to the true and first Inventor and Inventors of such Manufactures, which others at the tyme of makinge such tres Patents and Graunts shall not use, soe as alsoe they be not contrary to the Lawe nor mischievous to the State, by raisinge prices of Commodities at home, or hurt of Trade, or generallie inconvenient.

In broad terms, the Statute of Monopolies restricted the grant of patents to “any manner of new Manufactures” to the true and first inventor and imposed a limited term of 14 years for the grant of letters patent. By the early 1600s, the grant of letters patent and other privileges by the Crown had become controversial: they were being used merely as a convenient way for the Crown to raise revenue and were being granted in respect of products and processes that were already being used in the public domain, thereby harming trade and commerce. 2 The Statute of Monopolies sought to address these concerns by, among other things, limiting the grant of letters patent to particular subject matter (namely, any manner of new manufacture) and restricting the grant to a limited term. Following the passing of the Statute of Monopolies, the patent system in England continued to develop, eventually leading to the enactment of the Patents, Designs and Trade Marks Act 1883 (U.K.), which is the basis of the modern patent system in the United Kingdom and in Commonwealth countries.

Prior to Federation in 1901, each Australian colony had its own Patents Act that was modeled on the Patents, Designs and Trade Marks Act 1883 (U.K.). These Acts continued in force until the Australian Parliament enacted the Patents Act 1903 (Cth) pursuant to its legislative powers under Section 51(xviii) of the Commonwealth Constitution. The Patents Act 1903 (Cth) was replaced by Patents Act 1952 (Cth), which was in turn replaced by the Patents Act 1990 (Cth). The Patents Act 1990 (Cth), together with the Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth), came into operation on May 1, 1991.

The Patents Act 1990 (Cth) provides protection for two types of patents in Australia: the “standard” patent and the “innovation” patent. The main difference is that “innovation” patents have a shorter term of eight years and involve the lower threshold of an “innovative” step when compared to the prior art basis (as opposed to the “inventive step” required for standard patents).

The Patents Act 1990 (Cth) has undergone amendment several times since its enactment, including the reforms introduced by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth). These reforms apply largely in relation to patents requested for examination after April 15, 2013, and are designed to raise patentability thresholds to align more closely with the laws of overseas jurisdictions. More recently, the Australian Government passed the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Productivity Commission Response Part 1 and Other Measures) Act 2018 (Cth). These reforms involved, among other things, the introduction of an objects clause into the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), the phasing out of Australia’s “innovation” patent system 3 and amendments to the compulsory licensing scheme in Chapter 12 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth).

Australia is also signatory to a number of international treaties relating to patent rights, including the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, 4 the Patent Cooperation Treaty, 5 the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights 6 and various free trade agreements. Australia’s obligations under these treaties in relation to patent rights are reflected in the Patents Act 1990 (Cth).

Patent disputes are determined under the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) as interpreted by the case law that has developed under it, and its predecessor Acts. The development of modern Australian patent law has most closely followed that of the law of the United Kingdom, although there has been a measure of divergence from that law since that country joined the European Patent Convention in 1977. Often, during the course of patent trials, the parties inform the court of developments in the United States, the United Kingdom and Europe.

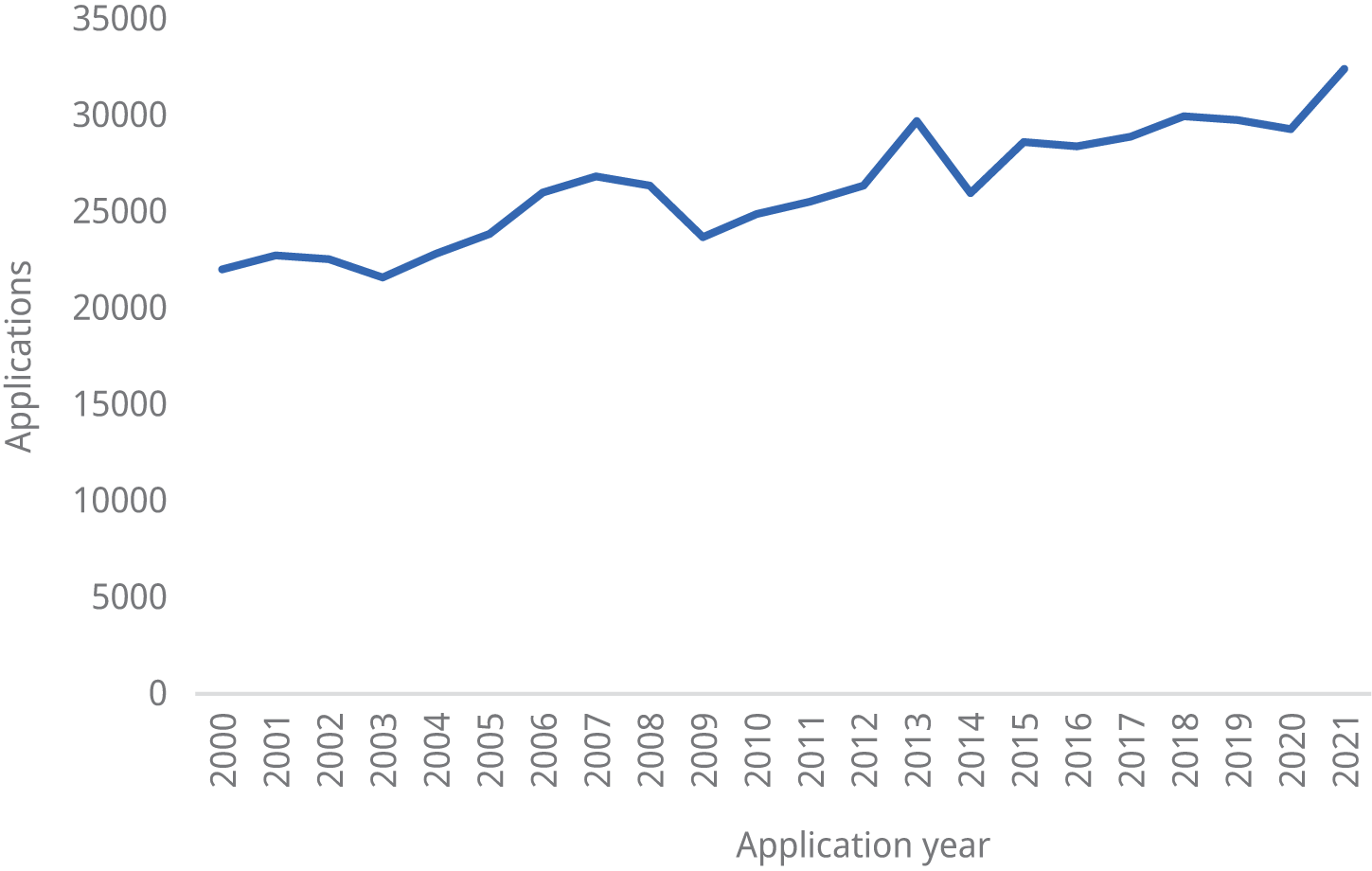

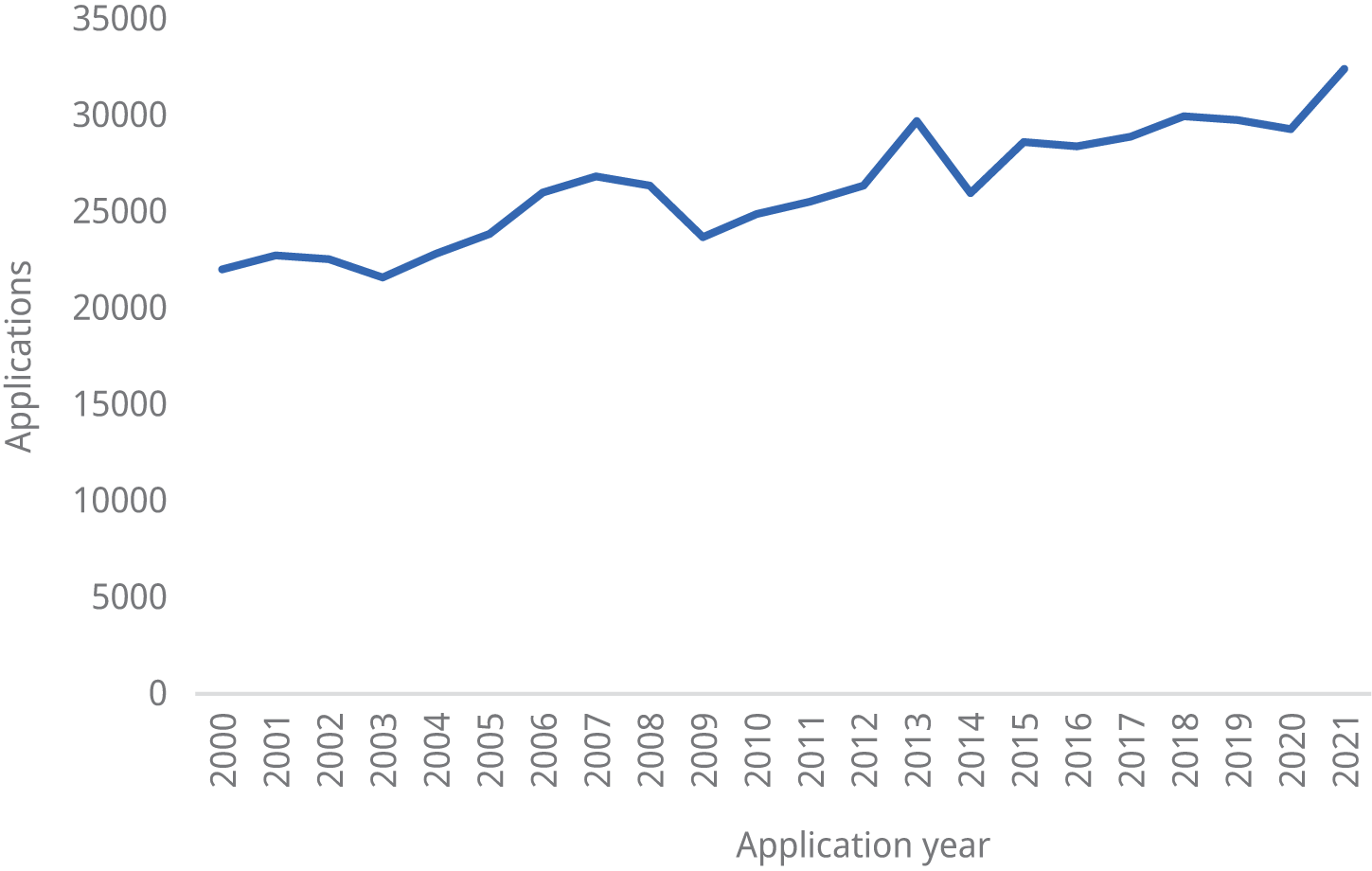

Figure 2.1 shows the total number of patent applications (direct and Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) national phase entry) filed in Australia from 2000 to 2021.

The Australian patent system is administered by the Australian Patent Office 7 (which is responsible for the administrative aspects of the patent system, including filing, examination and pre-grant “opposition” proceedings) and the Federal Court of Australia. 8

As noted above, Australia has recently abolished its second-tier “innovation” patent system, and applications for innovation patents ceased on August 26, 2021. The Australian Patent Office also facilitates the registration of overseas patent applications in Australia through the Paris Convention and the Patent Cooperation Treaty.

The Federal Court has jurisdiction to hear patent infringement, invalidity, entitlement and related disputes, together with appeals from the Australian Patent Office. It has jurisdiction in a number of other areas of law, including commercial and corporations laws, administrative law, industrial law, federal crime, admiralty and taxation. The Federal Court is located in the capital city of each state and territory, has a specialized panel of judges for patent matters and has a dedicated practice note for intellectual property matters, including patent disputes. 9

The Federal Court of Australia is the institution in which the validity of a patent may be challenged. Prior to grant, patents can be opposed in the Australian Patent Office. The available avenues for review of an invalidity determination depend upon the decision-maker, the type of decision and whether the determination was made pre-grant or post-grant.

The Intellectual Property Law Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) made a number of amendments to the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), including the internal grounds of invalidity and examination and opposition procedures in the Patent Office. The present section refers to the law that applies following those changes. However, it is important to be aware that, depending on the date on which an application was filed, an examination was requested, or the application was accepted, it will be necessary to consider the provisions in the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) prior to the amendments.

Following examination of a patent, the Commissioner of Patents may refuse to accept a request for a standard patent or specification. 10 The grounds of refusal for invalidity include a failure to comply with the internal requirements for invalidity (including sufficiency, best method and support) and that the invention is not a patentable invention (it is not a manner of manufacture, lacks utility, is not novel or does not involve an inventive step).

The decision of the Commissioner to refuse to accept a patent request or specification may be appealed to the Federal Court of Australia. 11

An examiner will issue reports if they reasonably believe that there are grounds of objection to a patent, and an applicant will be provided with opportunities to respond to and overcome the objections until the deadline for acceptance. In practice, most patents lapse rather than being formally refused.

Once acceptance of a standard patent has been advertised, the grant of the patent may be opposed by any person. The notice of opposition must be filed within three months from the date acceptance is published. 12 The grounds on which the grant may be opposed include the internal requirements for invalidity and that the invention is not a patentable invention. 13

If the Commissioner of Patents is satisfied that a ground of opposition exists on the balance of probabilities, the Commissioner may refuse the patent application. 14 However, the Commissioner must first give the parties a reasonable opportunity to be heard and (where appropriate) allow the applicant an opportunity to amend the specification.

The decision of the Commissioner following an opposition may be appealed to the Federal Court of Australia by either the opponent or the applicant. 15

The Commissioner of Patents may reexamine a standard patent if it has been accepted but not yet granted. The decision to reexamine pre-grant is at the discretion of the Commissioner but may occur, for example, following the identification of new prior art or the receipt of a notice from a third party. 16 Following grant, the Commissioner may reexamine a patent on their own initiative and must reexamine the patent if formally requested to do so by a third party in the approved form or following a direction from a court. 17 However, the Commissioner may not reexamine a patent if court proceedings are pending.

The Commissioner may refuse to grant the patent, or may revoke the patent, if the Commissioner makes an adverse report on reexamination (which includes on invalidity grounds) and is satisfied on the balance of probabilities that there is a lawful ground of objection to the specification. 18 However, the Commissioner must first provide the applicant or patentee an opportunity to respond to the report and be heard and (where appropriate) allow the applicant an opportunity to amend the specification.

The decision of the Commissioner to refuse an application or to revoke the patent following reexamination may be appealed by an applicant to the Federal Court of Australia. 19

A third party that has requested reexamination has no right of appeal of the decision of the Commissioner to the Federal Court. However, the third party may apply to the court for revocation of the patent or may seek judicial review, as discussed in Sections 2.2.2.4 and 2.2.2.5.

Allowing for the differences in procedure between them, the process for and the procedures governing claim construction in the Australian Patent Office are generally the same as in the Federal Court of Australia. In particular:

However, the Australian Patent Office only construes a claim in the context of a determination of validity or in claim amendment, not infringement (for a further discussion on claim construction with respect to infringement, see Section 2.5.1).

Expert evidence may be filed in the Australian Patent Office in the following invalidity proceedings:

Generally, expert evidence is given by way of declaration under the Patents Regulations. 23 While the Patent Office has the power to require witnesses (including expert witnesses) to give oral evidence at a hearing, such evidence is, in practice, rarely required. 24 The rules of evidence do not apply in the Patent Office. However, greater weight is likely to be given to expert evidence that complies with the rules of evidence on admissibility.

Expert evidence in the Australian Patent Office is generally directed to the following topics:

While claim construction is ultimately a matter for the Patent Office, the claims are read through the eyes of the skilled addressee in light of the specification as a whole and the CGK before the priority date. 25 Expert evidence can assist the Patent Office in placing itself in the position of a person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art at the time. 26 Expert evidence is particularly important where the words used in a patent claim or prior art document have a technical or special meaning in the relevant field. 27

The state of the relevant CGK for a patent or pending application is established by evidence from experts in the technical field concerning the extent to which certain information was known and accepted by others in the field. 28

An opinion from an expert as to whether an invention is obvious is unlikely to be helpful. This is because questions of obviousness and inventive step are ultimately for the court or Patent Office to determine, irrespective of the opinion expressed by any number of experts. 29

However, where obviousness is sought to be established, it is common for parties to set a design task for an expert representing the person skilled in the art. For example, an expert may be asked to solve the problem identified in the patent or pending application using only information that was CGK at the priority date.

When briefing an expert to provide evidence in relation to obviousness or inventive step, care must be taken to ensure that the evidence is not tainted by hindsight, either as a result of the witness applying hindsight or from the instructions given to the witness. Accordingly, where obviousness evidence is required, it is generally prudent for those taking the evidence to proceed in the following manner:

An appeal from a decision of the Commissioner of Patents (including to refuse acceptance or revoke grant) lies to a single judge of the Federal Court of Australia. 30 A party may appeal this decision of a single judge to the Full Court of the Federal Court only with leave.

An appeal from a decision of a state or territory supreme court lies to the Full Court Federal Court.

The question of whether leave to appeal to the Full Court should be granted may be decided by a single judge or may be referred to the Full Court. The grant of leave to appeal is discretionary, and relevant factors may include whether the decision is attended with sufficient doubt, whether substantial injustice will result from a refusal to grant leave and whether the appeal involves a question of public importance or of pure law. Where a party has unsuccessfully opposed the grant of a patent twice, there is limited scope for a further appeal. 31 Conversely, the grant of leave to appeal is more likely where the grant of a patent has been refused, as this would be determinative of the patentee’s rights. 32

An appeal from a first-instance court decision on invalidity (such as an application for revocation) lies to the Full Court of the Federal Court. 33 Leave to appeal is not required for a final decision on invalidity.

A party may seek special leave to appeal to the High Court of Australia from a decision of the Full Court. However, the grant of special leave to appeal such a decision is rare.

The Patent Office is an administrative decision-maker. A person aggrieved by a decision of the Commissioner of Patents that is of an administrative character may therefore seek judicial review in the Federal Court or Federal Circuit Court. The nature of a judicial review is more limited than an appeal and focuses not on the merits of the decision but on the legality of the decision and the processes followed. Grounds of judicial review include that the decision involved a breach of the rules of natural justice, a failure to observe required procedures, the absence of jurisdiction or authority, an improper exercise of power, an error of law or that it was induced or affected by fraud. 34

An affected person may also seek a merits review of certain specified decisions of the Commissioner in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. 35 However, this does not include the final decisions of the Commissioner on invalidity that have been discussed in this section.

An appeal from a decision of the Commissioner of Patents to the Federal Court of Australia must be filed within 21 days of the date of the decision unless an extension of time is granted. 36 The Commissioner is entitled to appear and be heard in any appeal against a decision of the Commissioner. 37 However, the Commissioner is not automatically a party to any appeal unless there is no other party opposing the appeal. 38

An appeal to the Federal Court from a decision of the Commissioner is not an “appeal” in the strict sense – it is in the Federal Court’s original jurisdiction and conducted as a hearing de novo. 39 This means that the court stands in the shoes of the Commissioner and makes the decision afresh. The court is not confined by the arguments or evidence that were before the Commissioner, including the grounds of invalidity. The court may receive fresh evidence and direct that the proceeding be conducted as it thinks fit. 40 Evidence that was before the Commissioner may be admitted with leave 41 but must also comply with the general rules of evidence.

The Federal Court may affirm, vary or reverse the decision of the Commissioner and may give any judgment or make any order that, in all the circumstances, it thinks fit. 42 While the Federal Court is generally confined to the subject matter of the controversy that was before the Commissioner, the court also has the power to direct the amendment of a patent application on an appeal. 43

This section has focused on the avenues for review of decisions relating to the validity of standard patents. Key differences in relation to the review of invalidity decisions relating to an innovation patent, by contrast, are that an innovation patent is examined only after grant and reexamined or opposed only after certification. Following examination, reexamination or opposition, the Commissioner of Patents may decide to revoke the grant of an innovation patent, including on invalidity grounds. 44 An appeal lies to the Federal Court of Australia in relation to a decision to revoke an innovation patent. Innovation patents are being phased out, with the last date for filing an application having been August 25, 2021.

Almost all patent infringement and revocation proceedings are heard in the Federal Court of Australia. As a matter of theory, state and territory supreme courts also have jurisdiction to hear such proceedings, although this rarely occurs. Appeals from decisions of the Commissioner of Patents, who is responsible for granting patents under the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), are heard by the Federal Court. All appeals from first-instance infringement and revocation decisions, or from Federal Court decisions made with respect to decisions of the Commissioner, must be heard by the Full Court of the Federal Court.

The Federal Court is composed of a Chief Justice and judges who are appointed from time to time. It is a national court with registries located in each capital city and operates under a policy known as the National Courts Framework. A key feature of the National Courts Framework is the organization of matters filed in the court into national practice areas (NPAs) and subareas. One of the NPAs is Intellectual Property, which has a subarea dedicated to disputes relating to patents and associated statutes. Presently, there are 15 judges who are allocated to the Patents and Associated Statutes subarea of the Intellectual Property NPA. Many of these judges have extensive experience in the conduct of patent trials, as a result either of their work in practice before being appointed to the court or since their appointment. As a general rule, once a case is allocated to a particular judge, that judge retains that case in their docket through the case management, to hearing and judgment.

Individual judges are principally situated in their local registry; however, they are able to hear matters filed in different state or territory registries. Each registry is staffed by registrars and support staff, including lawyers, senior coordinators, client service officers and court officers. In addition to providing operational support to the judges in each state, registrars perform statutory functions assigned to them by the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). These registrars often have expertise in intellectual property matters, including patents, and provide assistance to judges during the interlocutory phases of case preparation. Where the parties to a patent dispute agree to a mediation being facilitated by a registrar, a registrar with experience in patent cases will frequently be allocated. In addition, registrars will often provide assistance in the preparation of the joint expert report by facilitating the meeting of the experts. Furthermore, disputes relating to the production of documents or costs and other such matters may be delegated to registrars for adjudication. The registries also provide registry services to legal practitioners and members of the public, including by providing information regarding the practices and procedures of the court.

Individual judges of the Federal Court sit at first instance and also as appellate judges. Appeals from decisions of a single judge of the Federal Court, or from decisions of state or territory supreme courts, are heard by the Full Court of the Federal Court, the appellate division of the Federal Court. The Full Court is typically composed of three judges of the Federal Court who are selected for each appeal. Where an appeal is challenging the correctness of a previous decision of the Full Court, an expanded bench of five judges may be constituted.

Appeals from the Full Court of the Federal Court are heard by the High Court of Australia. The High Court is a separate court composed of a Chief Justice and six judges. In order to have an appeal heard by the High Court, parties are required to make an application for special leave to appeal. Special leave applications are determined on the papers or at short contested hearings usually heard by one or two judges of the High Court. If special leave to appeal is granted, the matter will be heard and determined by the Full Court of the High Court, which will usually be composed of between three and seven judges. There is no avenue of appeal beyond the High Court.

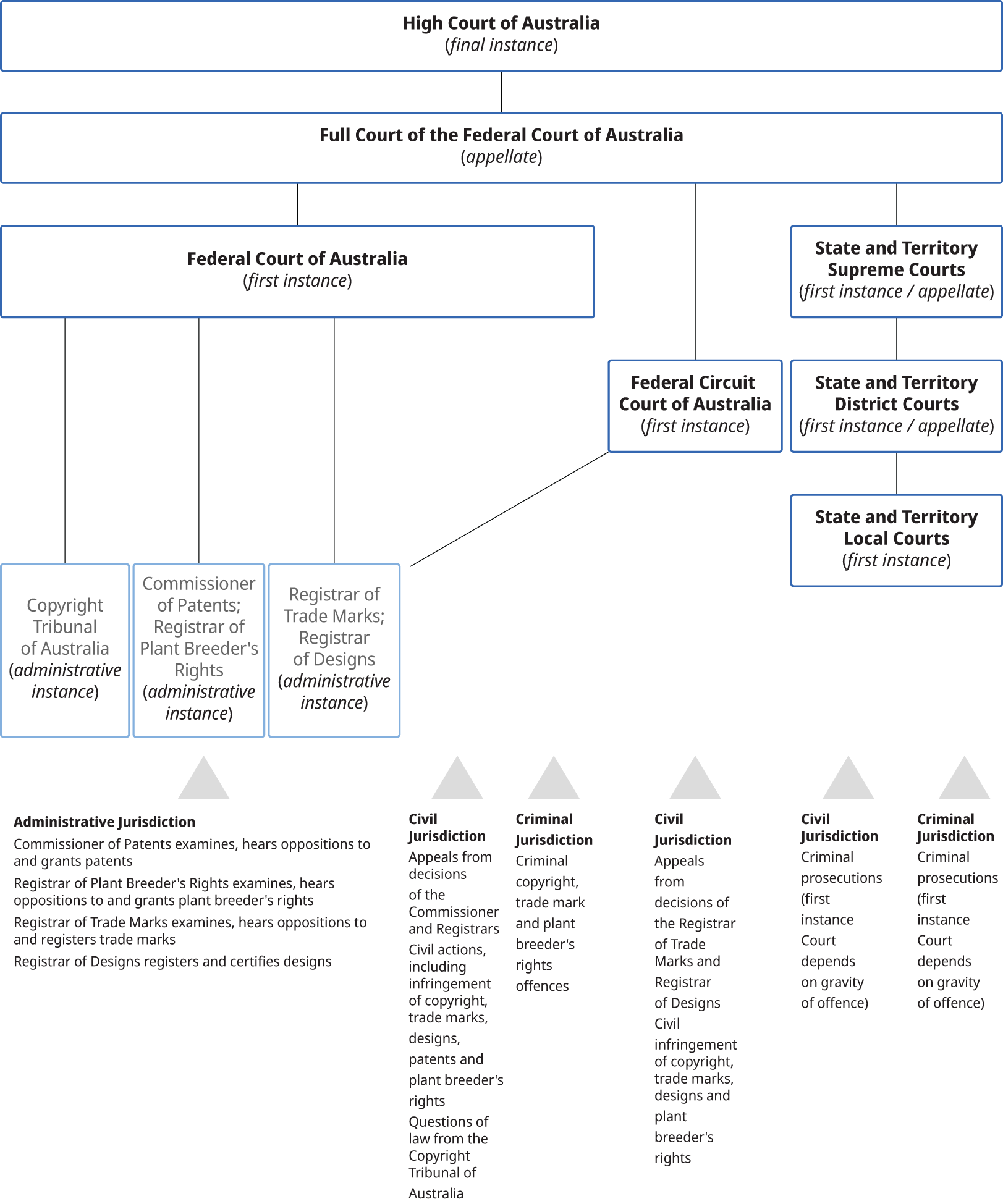

Figure 2.2 shows the judicial administration structure in Australia.

Judges of the Federal Court of Australia are appointed by the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia by commission. Judges are appointed from the ranks of qualified legal practitioners of significant standing in the legal community. They are most typically appointed from the ranks of barristers or, less frequently, solicitors, who have practiced law for decades before being appointed. All Federal Court judges must retire at the age of 70 years.

Judges of the Federal Court exercise the judicial power of the Commonwealth and are independent from Parliament and the executive branches of the government. As the Federal Court is a court created by Parliament under Chapter III of the Constitution, judges may not be removed from office except by the Governor-General on an address from both houses of Parliament in the same session on the ground of proven misbehavior or incapacity.

The Intellectual Property NPA is coordinated by a select group of national coordinating judges who have expertise in intellectual property law. These national coordinating judges are responsible for the operation and administration of the Intellectual Property NPA, including the Patents and Associated Statutes sub-area. This involves, among other things, overseeing the ongoing development of a program of education for judges and the profession.

In addition to its jurisdiction to review determinations of the Patent Office as to invalidity in relation to patent applications (see Section 2.2.2.4), the Federal Court is frequently asked to adjudicate allegations of invalidity in the context of proceedings seeking revocation of a granted patent or where invalidity is raised as a defense in infringement proceedings brought by the patentee or its exclusive licensee.

When patent invalidity cases are filed, they are allocated to judges in the registry of filing who are within the Patents and Associated Statutes subarea of the Intellectual Property NPA. This allocation principle is subject to:

Typically, complex patent matters, such as those involving pharmaceuticals or other complex scientific subject matter, are allocated to judges with significant experience in the field. As noted above in Section 2.3.1.1, and below in Section 2.6, the individual docket system means that, once a matter has been allocated to a judge, it is intended that the case will remain with that judge for case management and disposition.

If infringement proceedings are already in progress when proceedings alleging the invalidity of the same patent are commenced (either by cross-claim or otherwise), the invalidity proceedings will most likely be allocated to the docket of the judge hearing the infringement proceedings and the matters heard together, as in a single proceeding.

Proceedings seeking revocation of a patent for invalidity are usually commenced by pleadings. The applicant will typically commence proceedings by filing an originating application and statement of claim. The originating application will set out the nature of the orders being sought in the proceedings (e.g., a declaration that particular claims of a patent are invalid). The statement of claim will provide further detail about the invalidity challenge, including the grounds upon which it is alleged that the patent is invalid. In addition, the applicant must also provide particulars of invalidity setting out with more precision the basis upon which each of the grounds of invalidity is said to be established.

In response, the respondent patentee will file a defense to the statement of claim. In its defense, the respondent will either admit, deny or otherwise provide an explanation in response to the allegations contained in the statement of claim. The applicant will then be able to file a reply to the defense or, failing this, be taken to join issue and deny the allegations made in the defense.

Once the pleadings have been finalized and closed, it is typical for the preparation of evidence in the proceedings to be commenced. This topic is discussed in Section 2.6.7.

Expert evidence in patent litigation in the Federal Court of Australia is almost exclusively given on affidavit and by way of joint report. Expert evidence is expected to comply with the requirements set out in the applicable practice note (at the time of writing, the Expert Evidence Practice Note (GPN-EXPT), dated October 25, 2016) as well as the relevant rules of court. 45 These requirements place particular focus on the importance of the expert’s independence as well as matters going to admissibility and the manner in which experts’ evidence will be prepared and presented at trial. The practice note specifically requires every expert witness to read the Harmonised Expert Witness Code of Conduct 46 and agree to be bound by it. Unlike in the Patent Office, the rules of evidence apply in Federal Court proceedings.

Where an allegation of invalidity is raised in answer to an application for preliminary injunctive relief, expert evidence bearing on questions of construction of the specification or the contents of prior art documents will usually be given on affidavit. Cross-examination is rare in interlocutory applications of this kind.

In the case of invalidity evidence to be received at trial, the following procedural matters should be noted:

Expert evidence relating to invalidity will generally pertain to the same issues discussed at Section 2.2.2.3 in relation to Patent Office proceedings (in particular, evidence assisting the court in understanding the patent specification, the prior art, the state of knowledge – including CGK – in the relevant field at the priority date). In cases relating to older patents, there may be expert evidence establishing that a particular document would have been ascertained and regarded as relevant to a particular technical problem by the skilled addressee.

This section focuses on claim construction in the Federal Court of Australia, given that patent matters are primarily conducted in that jurisdiction.

The proper construction of a patent is a question of law. The construction of the patent in question is important to most issues in patent disputes and can often be determinative of them. In particular, the proper construction of a patent may:

Argument about the proper construction of a patent generally takes place at a final hearing and at the same time as argument about infringement, invalidity and associated legal and factual issues. Determination of the proper construction of a patent before a hearing on infringement and invalidity is rare. However, the court may choose to follow this course, especially if this leads to efficiencies in how the case will be run.

One consequence of the construction of a patent being determined at the same time as issues of infringement and invalidity is that, often, evidence is prepared and argument occurs based on more than one possible claim construction. It is common for the alleged infringer to argue that it wins the case on any construction; for example, if the construction is X, then there is no infringement, but if the construction is Y, then the claim is invalid .

That said, the alleged infringement or prior art is to be ignored when construing the patent. Although the forensic contest in any patent dispute will raise the particular construction issues to be resolved, a patent must “be construed as if the infringer had never been born” 48 and without “an eye to the prior art.” 49

The court does not need to adopt a construction put forward by any of the parties or their expert witnesses and may come up with its own construction. Further, as there are often multiple construction issues in a case, it is common for different construction issues to be determined both in favor of and against a party.

The construction of a patent is often an issue on appeal. While an appeal court may give some deference to a trial judge’s construction, it generally will not hesitate to adopt and apply a different construction if it perceives that the trial judge’s construction involved error(s). This is because the construction of a patent is a question of law, and, generally, the appeal court is in as good a position as the primary judge to construe the patent.

When filing originating documents alleging infringement or invalidity, a party does not generally need to indicate its position as to how the claim is to be construed.

Nonetheless, in some cases, the court may require the parties to indicate their position on construction at an early stage of the proceeding either directly (e.g., by requiring it to plead the various consequences for infringement and invalidity if a particular construction is adopted) or indirectly (e.g., by requiring the filing of position statements on infringement or a claim chart regarding invalidity). 50

The principles of claim construction are settled. Disputes about construction usually concern the language of a particular claim rather than matters of principle. The determination of the proper construction of a patent specification including the claims is based on how the person skilled in the relevant art would understand it. Such a person is regarded as being neither particularly imaginative nor particularly inventive (or innovative).

The court seeks to determine how the skilled addressee would have understood the patentee to be using the words of the claim in the context in which they appear. The construction of a patent is objective in the sense that it is concerned with what the skilled addressee would understand from the patent, not what the patentee meant to say. The claims must be construed in the context of the specification read as a whole and in light of the CGK. However, it is not permissible to alter the words of a claim by adding glosses drawn from other parts of the specification. Further, if a claim is clear, it is not to be made obscure simply because obscurities can be found in parts of the specification.

It is often said that claims should be given a purposive – not a purely literal – construction and that a too “technical” or “narrow” construction should be avoided. 51 In construing claims, “a generous measure of common sense should be used,” and a literal construction devoid of practicality and context is to be avoided. 52 Claims should be construed while bearing in mind that the invention is to be put to practical use. A claim should not be construed to give a foolish result. Where possible, different claims in the same patent should be construed in such a way that their scopes are different. This is known as the presumption against redundancy.

The patentee may provide a “dictionary” of the jargon used in the claims, in which case that dictionary definition of the term generally applies. There are two kinds of terms for which a dictionary may be used: words that otherwise do not appear to have a positive meaning and common words that are to be given a different meaning.

Construction is a matter for the court. Although expert evidence regarding the meaning that the skilled addressee would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases may be submitted, it is for the court to interpret words bearing ordinary meaning. Indeed, the court can construe the claims without reference to expert evidence.

Despite this, it is relatively common for parties to adduce expert evidence that solely concerns the meaning a skilled person would attribute to a claim that does not contain technical or scientific terms. Often, however, the court gives such evidence little weight, although it is rare for the court to hold that it is inadmissible.

The general rule in Australia is that the file wrapper is neither relevant nor admissible in construing the claim. The only qualification to this is Section 116 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), which, in interpreting a complete specification as amended, allows the court to refer to the specification without amendment. Besides this narrow exception, Section 116 does not permit recourse to other documents on the Patent Office file.

The Federal Court of Australia and the state and territory supreme courts have jurisdiction to hear patent infringement matters. The Federal Court is granted jurisdiction directly from the Patents Act 1990 (Cth). 53 In addition, state and territory supreme courts, as “prescribed courts,” are also granted jurisdiction directly from the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) in respect of a number of discrete matters (this relevantly includes infringement proceedings). 54

Patent infringement proceedings are typically commenced in the Federal Court. This is a national jurisdiction with numerous judges who have extensive patent litigation expertise, often including practice at the bar prior to being appointed. First-instance proceedings in the Federal Court are heard and determined by a single judge. There are no jury trials for patent cases in Australia.

A party can commence patent proceedings before the Federal Court sitting in any Australian state or territory. The procedural rules and processes are standardized across Australia. Typically, a party will choose to commence a proceeding in the Federal Court registry that is in the state or territory in which they operate or where their legal representatives are located. Due to the standardized procedural rules and depth of experience of the Federal Court judiciary across the national Federal Court jurisdiction, there is no perceived benefit or disadvantage in commencing a proceeding in any particular venue.

Post-grant patent revocation proceedings can also be initiated in the federal (most commonly) or supreme courts. These can be commenced by a party seeking to “clear the path” ahead of the commercialization of a technology. However, in most instances, post-grant revocation is brought as a cross-claim to an infringement proceeding.

In the Federal Court, there are a number of NPAs, one of which is Intellectual Property, which includes the subarea of Patents and Associated Statutes. 55 This subarea includes:

There are approximately 54 Federal Court judges across the Federal Court. All Federal Court judges sit in multiple national practice areas although only 15 sit in the Patents and Associated Statutes subarea, as noted on the Federal Court portal. 56

The Federal Court operates an individual docket system, under which a case is allocated to a judge from filing to final hearing. Proceedings relating to patents are subject to the Intellectual Property Practice Note (IP-1). 57 This practice note provides guidelines for how patent proceedings – both validity and infringement – must be case-managed, including the use of agreed primers and position statements on infringement.

Federal Court judges actively manage cases in their docket, and parties are required by Federal Court legislation to conduct proceedings as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible. 58 Consistent with its drive for efficiency, the Federal Court is increasingly limiting the scope of pre-trial processes, in particular discovery. The docket judge sets a timetable for steps such as discovery, evidence and pre-trial steps and will seek to minimize the extent of interlocutory disputes about these procedural steps. Although it varies depending on the nature of the case, the docket judge will often, at an early stage, set the matter down for a final hearing, which then provides a practical end point to the timetable for the steps of discovery, evidence and pre-trial matters.

Parties may be represented by lawyers, being either barristers, solicitors or, as is often the case, a combination of both. If a party is a natural person, they may also choose to represent themselves. Corporate parties must be represented by lawyers; however, with the leave of the court, they may be represented by a nonlawyer.

In order to commence proceedings in the Federal Court of Australia for patent infringement or for the revocation of a patent on the grounds of invalidity, a party must file an originating application setting out the form of relief sought. 59 Generally, the originating application will be accompanied by a statement of claim or affidavit, setting out further information regarding the basis of the claim. 60 The applicant must also file a “genuine steps statement” specifying the steps taken to resolve the issues in dispute prior to instituting proceedings. 61 Generally, this is satisfied by a patentee sending a letter of demand before commencement and allowing an appropriate period (which may be only a short period for urgent matters) for the other party to respond. These documents must be served on the other party in accordance with the court rules. 62

A respondent in patent infringement proceedings must file a defense to the claim within 28 days of service of the statement of claim. 63 However, the timing of the filing of the defense may, in some cases, be varied by order of the court. For example, a respondent may require further time to respond, particularly if they require further particulars of infringement from the applicant prior to being able to respond to the claim.

Alternatively, in certain circumstances, the Federal Court also allows parties to file a concise statement, which is limited to a statement of five pages, setting out the key facts giving rise to the claim, the relief sought, the primary legal grounds and the alleged harm suffered by the applicant. 64

Importantly, in Australia, it is possible for an applicant to seek an interim and interlocutory injunction in relation to potential patent infringement. The applicant may approach the duty judge of the Federal Court for orders expediting the filing and service of the originating application and pleadings to facilitate an urgent hearing of the application for interlocutory relief.

Specific rules of the Federal Court of Australia govern the conduct of intellectual property cases. Those rules are supplemented by the Intellectual Property Practice Note (IP-1), which, when read with the Central Practice Note: National Court Framework and Case Management (CPN-1), sets out the key principles of case management procedure applied by the court.

The rules concerning the management of patent cases are structured to have a strong emphasis on the quick, efficient and as-inexpensive-as-practicable disposition of each matter. The key objective of case management is to reduce costs and delay so that there are fewer issues in contest, promote the effective use of expert evidence and ensure both that there is no greater factual investigation than justice requires and that there are as few interlocutory applications as necessary for the just and efficient disposition of cases.

The court recognizes that proceedings in the Patents and Associated Statutes subarea of the Intellectual Property NPA will vary in complexity, and so a flexible approach is taken to the conduct of proceedings, which enables practitioners to tailor the conduct of the case according to need. Case management hearings are integral to case management; they are conducted by the docket judge, and one of their aims is to identify the genuine issues in dispute between the parties at the earliest stage. At the first case management hearing, the parties’ legal representatives are expected to have an understanding of the case such that they can assist in developing directions for the conduct of the matter to ensure that it is swiftly and economically brought to trial.

The following matters routinely arise in discussion during the course of the initial and any subsequent case management hearings:

The court will seek to set down the proceedings for a final hearing as soon as it becomes apparent when the parties will be in a position to complete the necessary pre-trial steps.

Practitioners are encouraged to discuss the proceedings from an early stage to determine whether alternative procedures that will facilitate the efficient disposition of proceedings can be adopted by the court. The court has the power to appoint:

As a matter of practice, these steps are rarely taken in patent cases during the liability phase of the proceedings.

A regular topic for discussion at case management hearings is whether, having regard to the manner in which the dispute between the parties has developed, the proceedings can be more efficiently conducted by either or both:

After any expert evidence in chief has been filed and answered, the court will frequently direct that the experts meet and prepare a joint expert report. This process facilitates the commencement of a direct dialogue between the experts that is intended to ensure that the subject matter of their oral evidence is confined to relevant matters that are genuinely in dispute. Experience has demonstrated that the process of preparing the joint expert report frequently eliminates semantic or peripheral disputes that otherwise appear significant in written reports.

After most of the preparatory steps have been taken, the docket judge will conduct a more detailed pre-trial case management hearing, wherein the conduct of the hearing will be considered. During this hearing, the parties discuss the timetable for the hearing, whether witnesses can appear by video link or in person, the conduct of the joint expert evidence by the giving of concurrent evidence (as to which, see Section 2.6.7.4), the order of submissions and other practical matters.

When a proceeding for patent infringement or revocation is filed in the Federal Court of Australia, it will typically be allocated by the court to a docket judge, who will conduct all case management hearings of the proceedings and will also conduct the final hearing. There are a number of advantages of this docket system, including that the trial judge is familiar with the matter by the time of the final hearing. It is also a useful discipline for the parties that the judge hearing their procedural applications throughout the proceedings is the same judge who will be conducting the final hearing.

Generally, a judge from the Patents and Associated Statutes subarea (that is, a judge with experience in patent cases) will be allocated to the patent infringement or revocation proceeding as the docket judge.

The docket judge will determine when to set the hearing date for the final trial in the proceedings. In some cases, this may be done at an early stage of the proceeding. However, it is not uncommon for a hearing date to be set later in the proceedings, such as after the pleadings or after evidence has been filed.

The Federal Court of Australia has equitable jurisdiction to grant temporary injunctions restraining an alleged infringer from engaging in certain conduct until the substantive merits of a proceeding can be determined. 65 Such injunctions are referred to as interlocutory injunctions or, if they are granted pending an application for an interlocutory injunction, interim injunctions.

Such injunctions can be a useful tool for patentee applicants to preserve the status quo in the market during the preparation period for trial and hearing and while judgment is reserved. It is important to bear in mind that the “price” of an interlocutory or interim injunction is the applicant’s giving of the “usual undertaking as to damages” to the court – a matter which is discussed in Section 2.6.4.3 of this chapter. Another matter for practitioners to bear in mind is that, in lieu of granting an interlocutory injunction, the court may be willing to grant an early final hearing. Such a course may benefit either or both parties, and it removes the need for the patentee applicant to give the usual undertaking as to damages. It is also likely to hasten the final determination of the dispute, including by removing the potential for delay arising from any appeal of the court’s decision to grant or refuse an interlocutory injunction.

Applications for interlocutory injunctions should be brought as quickly as reasonably practicable after an applicant becomes aware of allegedly infringing conduct. The granting of interlocutory injunctions is at the court’s discretion. Factors that militate against the grant of equitable relief generally apply equally with respect to interlocutory injunctions, such as laches (delay). Further, the failure of an applicant to move with haste to seek an interim or interlocutory injunction tends to undercut any submission by the applicant that an interim or interlocutory injunction is urgently required to maintain the status quo to protect the applicant’s position prior to the substantive determination of the rights of the parties.

In circumstances where interlocutory injunctive relief needs to be sought urgently (subject to the practicalities of obtaining evidence to establish a prima facie case of patent infringement), practitioners should be familiar with paragraphs 3.1–3.5 of the Intellectual Property Practice Note (IP-1). It provides that, where urgent relief is sought, once appropriate documentation has been prepared in support of such an application, the associate (or “clerk”) of the duty judge should be contacted in order to allocate a hearing time for such an application. The allocated Federal Court duty judge changes from time to time, and they are identified on the Federal Court daily list on the Federal Court’s website.

When deciding whether to grant an interlocutory injunction, the court will consider whether the applicant has established a prima facie case (often framed by asking whether there is a serious question to be tried) and whether the balance of convenience favors granting the interlocutory injunction). 66 Almost invariably, the applicant will also be required to give an undertaking to the court as to damages. These concepts are outlined in more detail below.

When hearing an application for an interlocutory injunction, the court is not making a final determination as to the parties’ rights and the merits of the case. Instead, the court will seek to determine, on a preliminary basis, the strength of the applicant’s case. The applicant does not have to prove that it is more probable than not that it will make out a claim of infringement at a trial of the proceeding – merely that it has a sufficiently strong case in the circumstances to justify the grant of the interlocutory injunction to preserve the status quo pending trial. As in any substantive proceeding, evidence – and often expert evidence – will be required to make out a prima facie case. However, given the often urgent circumstances in which relief will need to be sought, the evidence may be less detailed and expressed in a more contingent way than would be the case at trial.

While a patentee need only establish a prima facie case, or that there is a serious question to be tried, the stronger the case of the applicant, the more likely it is that the balance of convenience will favor the granting of an interlocutory injunction, as discussed further in Section 2.6.4.2.

As in all patent proceedings, when defending against an application for an interlocutory injunction based on a claim of patent infringement, an alleged infringer may seek to challenge the validity of the patent. However, if all that a respondent can establish is that it has an arguable case that the patent is invalid, that will be insufficient to displace the applicant’s prima facie case of patent infringement. The respondent will need to establish a sufficiently strong case that the patent is invalid with the result that it cannot be said that the applicant has made out a prima facie case, given that an invalid patent cannot be infringed.

When considering whether the balance of convenience is in favor or against the granting of an interlocutory injunction, the court considers the respective impacts of an interlocutory injunction on the applicant, the respondent and third parties. As referred to at Section 2.6.4.1, the balance of convenience is considered in light of the strength of the applicant’s case. All other matters being equal, a stronger case will suggest the balance of convenience lies in favor of granting an injunction than a weaker case.

As a starting point, a key factor to consider in determining where the balance of convenience lies is whether damages would be an adequate remedy for the applicant. That is to say, determining whether, if an interlocutory injunction were not granted and the respondent carried out the actions of which the applicant complains, the applicant would be adequately compensated for that conduct by an order for damages if the matter is ultimately determined in the applicant’s favor. If damages are an adequate remedy, an interlocutory injunction will not be granted because there is no need to preserve the status quo pending trial.

Factors that militate against such a finding include (a) the respondent not being in a financial position to pay any damages awarded, (b) the likely difficulty in quantifying damage, (c) whether some of the damage likely to be suffered by the patentee is unlikely to be recoverable as damages for patent infringement, and (d) the irreversibility of the effect on the applicant of the respondent’s conduct even if the respondent is ultimately injuncted at trial (e.g., if the respondent’s entry into a market will irrevocably change the nature of the market).

In respect of pharmaceutical patents, the operation of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, being the vehicle by which the Australian Government subsidizes the purchase of pharmaceutical products in Australia, has important effects on the balance of convenience. Under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme legislation, the entry of a second brand of pharmaceutical product into the Australian market has the effect of reducing the price at which the first brand of pharmaceutical product may be sold by the patentee in Australia and, therefore, the quantum of the subsidies paid by the Australian Government under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. The court may be willing to grant an interlocutory injunction to restrain the exploitation of the second brand on the basis that, if the second brand enters the market, the patentee will suffer irrevocable damage because the price at which the patentee may sell the first brand will be reduced. 67

As well as considering how the applicant will be affected if an interlocutory injunction is not granted, the court will also consider the effect upon the respondent and third parties if the interlocutory injunction is granted. In so doing, the court will bear in mind that the respondent and third parties may have the benefit of the usual undertaking as to damages given by the applicant to the court. If the interlocutory injunction would, in practical effect, bring the dispute to an end (e.g., because the respondent’s business would be irreversibly affected, or the fast- moving nature of the market is such that, by the time the dispute is ultimately determined, the respondent’s product will no longer be commercially valuable), then this is a matter that can weigh against granting the injunction or at least suggest that the applicant has to make out a stronger prima facie case. Equally, if third parties would be adversely affected in a way that is unlikely to be compensated by the usual undertaking as to damages, then this can also be a matter weighing against an interlocutory injunction.

Ultimately, the balancing exercise is a discretionary one and an exercise that depends on the particular circumstances of each case.

If an applicant seeks an interlocutory injunction, it will almost always be required to give an undertaking as to damages. The form of the undertaking is as set out in the Usual Undertaking as to Damages Practice Note (GPN-UNDR). 68 In essence, the undertaking requires the applicant to undertake to the court to submit to such order as the court may consider to be “just” for the payment of compensation to any person (whether or not that person is a party) affected by the operation of the interlocutory injunction and to pay such compensation. That is, if at the final hearing (and after exhausting appeals) the applicant is unsuccessful in establishing an entitlement to a final injunction for patent infringement, it will be required to compensate those who have been adversely affected by the interlocutory injunction, which may be the respondent and any third parties, in the period in which it operated.

In pharmaceutical patent matters, the Australian Government has adopted a practice of making substantial claims on the usual undertaking as to damages in circumstances where a patentee applicant has succeeded in obtaining an interlocutory injunction to restrain exploitation in Australia of a second brand of the patentee’s product but has ultimately failed (whether at trial or on appeal) to secure a final injunction.

Claims on the usual undertaking as to damages in the context of pharmaceutical patent cases have tended to become protracted and difficult, with the result that it cannot be assumed that claims on the usual undertaking as to damages will be successful. This is relevant to assessing the balance of convenience.

It may be the case that a patentee applicant becomes aware that a respondent is taking preliminary steps toward undertaking actions that would infringe a patent, but the respondent has not yet undertaken any act that infringes the patent. In that case, an applicant can seek an interlocutory injunction on a quia timet basis – that is, an injunction to stop threatened patent infringement. The same principles as outlined above apply, but, in this case, the applicant will also have to establish with some degree of probability that a respondent intends to ultimately do something that will infringe the patent. Quia timet injunctions are often sought in the context of pharmaceutical patents, where the highly regulated nature of the market is such that certain public steps have to be undertaken before a product can be launched on the market.

This section focuses on discovery processes in the Federal Court of Australia, given that patent matters are primarily conducted in that jurisdiction. Discovery is one type of court-mandated process that requires one party to litigation to disclose documents (or the existence of documents) to another. 69 Three other court-mandated document disclosure processes are: notices to produce and subpoenas, which are addressed briefly in Section 2.6.5.4, and preliminary discovery, which is addressed in 2.6.5.5.

Discovery in the Federal Court is governed by Part 20 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) as elucidated in the Federal Court’s Central Practice Note: National Court Framework and Case Management (CPN-1) Part 10, the Intellectual Property Practice Note (IP-1) paragraphs 6.14–6.16 and 9.1, and the Technology and the Court Practice Note (GPN-TECH) Part 3, which all also relate to the court’s processes regarding discovery.

Discovery may only occur by order of the court. 70 An order for discovery will only be made if it would “facilitate the just resolution of the proceeding as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible.” 71 That is, there is no right to discovery, and the court is not bound by any agreement between the parties regarding discovery. A court may refuse to order discovery, amend its scope or defer consideration of it until a later point in the proceeding. If a party seeks discovery in advance of all parties filing and serving their affidavit evidence, it is likely that the party will need to justify to the court why discovery should be ordered at that stage of the proceeding. The court may consider that the goals in Rule 20.11 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) are more likely to be achieved if discovery is ordered after all parties have filed and served their affidavit evidence. By adopting such a course, the burden of discovery may be minimized on the basis that any specific gaps in the evidence that need to be filled by way of discovery are more likely to be known. 72

“Standard discovery” refers to a party being ordered to produce all documents that are directly relevant to the issues raised on the pleadings that can be located after a reasonable search. The burden of such discovery can be significant. Central Practice Note paragraph 10.7 states that discovery should be proportionate to the nature, size and complexity of the case. However, the usual course in patent matters is for parties to negotiate “categories” of discovery, in which documents answering certain specific descriptions are sought. This is known as “nonstandard discovery” and is dealt with in Rule 20.15. For example, a category might seek documents recording or evidencing the steps undertaken in a particular manufacturing process where that would be relevant to proving infringement of a method or process claim.

There is no formal process for negotiating discovery categories. Usually, at a suitable stage of the litigation, parties will exchange correspondence outlining the categories they seek and then negotiate to reach agreement, for example, on the wording of those categories and the timing of document production. If agreement cannot be reached on some issues, the matter is usually brought before the docket judge by way of an interlocutory application, supported by an affidavit or a list of correspondence or undisputed documents under Rule 17.02. A judge will expect parties to have attempted to resolve differences regarding the categories as far as possible before ruling on the categories to be ordered. The judge will also expect the parties to have determined a suitable timetable for production – that is, to have considered how long the discovery process is likely to take given the scope of searches, investigations and reviews of the documents that need to be undertaken.

A party may oppose categories of discovery sought by another party on various bases. Grounds often include that (a) the documents sought are not directly relevant to an issue in the proceedings, (b) the documents are not necessary for a party to prove its case or impugn the case of its opponent, (c) the request is “fishing” (e.g., a speculative attempt to locate documents that would allow the requesting party to plead a new case), (d) the category is unnecessarily broad or is oppressive in that it would be unreasonably burdensome for the receiving party to comply with the category, and (e) the category would only produce documents that would be privileged, and there is no reasonable submission that such privilege has been waived. These matters are usually resolved at a hearing by reference to the pleadings; however, in contending that a category is oppressive, parties tend to file affidavit evidence from a solicitor outlining the scope of searches, investigations and reviews of documents required to satisfy the category. Notwithstanding such evidence, the court may order discovery in the category on the basis that the party need only conduct a reasonable search for documents as set out in Rule 20.14(3).

Unless otherwise ordered, a party must undertake a reasonable search for documents falling within the scope of any discovery categories ordered that are in its possession, power or control. Rule 20.14(3) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) outlines matters to consider when determining what constitutes a “reasonable” search in the particular circumstances of a proceeding.

There are two distinct steps in giving discovery: (a) the provision of a list of documents and (b) the production of the documents themselves. Rule 20.17(1) provides that a party “gives discovery” to another by providing a list of documents in accordance with Rule 20.18. A list of documents is prepared in the form of Federal Court Form 38, which is available from the Federal Court website. The list of documents must be sworn or affirmed by a suitable representative of a party: that is, someone with sufficient knowledge regarding the documents to which the list of documents relates. 73 Rule 20.17 provides that a list of documents must outline, in some degree of detail, the documents falling within the categories that are or were in a party’s possession or control. Where a document is no longer, but once was, in the party’s possession or control, an explanation must be given as to when and how the document left the party’s possession. The list of documents must also set out documents over which a party claims privilege.

Rule 20.32 provides that a party may seek an order from the court for the production of documents referred to in a list of documents. Such an order is usually made prospectively at the same time as other orders regarding discovery. The usual course is for copies of documents to be produced electronically from one party to another unless there is some particular reason for some other order (e.g., if the authenticity of a document is disputed, it may be necessary to produce the original version of the document).

A party’s discovery obligations are ongoing. 74 That is, after the provision of the list of documents occurs, a party is under an ongoing obligation to notify the other party if it uncovers a document that is within the discovery categories ordered but which is not in the list of documents. This may be due to oversight or because the document was created after the list of documents was created. However, a party does not have to produce privileged documents that are created after the proceeding commenced. 75

There are two bases on which a party can seek to restrict production of a document, whether in whole or in part (i.e., by masking parts of the document).

First, a party may refuse to produce a document on the grounds of legal professional privilege or public interest privilege. 76 Procedurally, the usual course in relation to disputed claims of privilege involves (a) a party, in its list of documents, asserting that a document is privileged from production; (b) if there is a dispute about the claim of privilege (e.g., on the basis that such a document could not be privileged, or that privilege in the document has been waived either expressly or implicitly), the other party filing an interlocutory application seeking an order compelling production of the document, for example, under Rule 20.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), supported by an affidavit or a list of correspondence or undisputed documents under Rule 17.02; and (c) the court deciding whether to grant the order compelling production of the document at a hearing.

Second, a party may seek to restrict production of a document on the basis of commercial confidentiality. Often, in patent proceedings, the litigants will be competitors. Documents produced may disclose commercially confidential matters. The usual course is for parties to negotiate a suitable protocol for dealing with such documents prior to production. For example, the parties may agree that the documents are only to be produced to external lawyers and counsel and to expert witnesses, but not to representatives of the party themselves. If the parties are unable to agree on a suitable protocol for dealing with confidentiality, it may be necessary to seek orders dealing with such issue from the docket judge.

The Federal Court of Australia encourages flexible and alternative ways of obtaining evidence that a party may otherwise seek by way of discovery. Examples of this in a patent context are product and process descriptions. In the context of proving infringement of a product or process claim, it may often be difficult for a party to know which documents to seek from the other or to prove from documents alone whether such a process infringes all the integers of a claim. Intellectual Property Practice Note (IP-1) paragraphs 6.14–6.16 state that, in such a situation, a court may order an alleged infringer to prepare and serve a sworn statement from a suitably knowledgeable person as to the nature of the alleged infringer’s product or process to allow the other party to make out its case on infringement or to seek documents in a more targeted manner.

Notices to produce are another process by which a party can seek documents from another party. While the precise boundaries between a notice to produce and discovery by way of categories can appear unclear, the primary difference is that notices to produce are a more targeted process and must be directed to the production of specifically identified documents. There are two kinds of notices to produce. The first is requests for documents referred to in a party’s pleading or affidavit, which occurs without the supervision of the court unless there is a dispute as to the notice (e.g., a dispute as to whether the pleading or affidavit in fact “refers to” the document sought in the notice). 77 The second is orders for the production to the court of certain documents. 78 Production under Rule 30.28 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) is not limited to during trials, and a practice has developed of parties seeking production of documents before the registrar under Rule 30.28 at any time in a proceeding. Documents sought under this rule are not only limited to documents referred to in an affidavit or pleading. 79

Finally, documents may be sought from nonparties by way of subpoenas for the production of documents. 80 Subpoenas are governed by Part 24 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) and are also addressed in Parts 1–10 of the Subpoenas and Notices to Produce Practice Note (GPN-SUBP). Subpoenas are a substantial topic in their own right, and it is beyond the scope of this section to deal with them in any detail. Like discovery, there is not a “right” to a subpoena. Subpoenas may only be issued with leave of the court. 81 Subpoenas are issued by the court, not a party, so compliance is owed to the court, not the party seeking the subpoena. Given that a failure to comply with a subpoena constitutes contempt of court, 82 and subpoenas impose burdens on nonparties to the litigation, there are detailed and strict rules regarding the form and service of subpoenas. 83 Like discovery, subpoenas will usually seek the production of categories of documents. However, those categories will usually need to be more confined and prescriptive than categories sought on discovery, owing to the fact that the subpoena recipient is a nonparty and will not be familiar with the issues in a proceeding.

A further difference between discovery on the one hand and notices to produce and subpoenas on the other is that a category for discovery may be more broadly described and a party giving discovery has the obligation to search for and produce all documents relevant to the proceedings within that category. A notice to produce and a subpoena generally require greater specificity of description of the documents sought and the recipient is entitled to read the described category sought narrowly and produce only documents strictly within that category.

Rules 7.22 and 7.23 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) provide for two types of pre-action discovery. Rule 7.22 allows a prospective applicant to obtain discovery from a third party to ascertain the description of a prospective respondent, subject to satisfying the jurisdictional prerequisites set out in Rule 7.22(1) and the court’s discretion in Rule 7.22(2). Rule 7.23 allows a prospective applicant to obtain discovery from a prospective respondent of documents directly relevant to the question of whether the prospective applicant has a right to obtain relief, subject to satisfying the jurisdictional prerequisites in Rule 7.23(1) and the court’s discretion in Rule 7.23(2). That is, subject to those matters, Rule 7.23 allows a prospective applicant to “fish” for a case against a prospective respondent.

Each of the jurisdictional prerequisites in Rule 7.23(1) must be satisfied. A prospective applicant must satisfy the court that it reasonably believes that it “may” have the right to obtain relief in the court from a prospective respondent and that, after making reasonable inquiries, it does not have sufficient information to decide whether to start a proceeding in circumstances where the documents sought by discovery would assist in making the decision.

The mechanism under Rule 7.23 can be useful for obtaining documents to determine whether a product being sold in Australia is being made using a patented process.

In the Federal Court of Australia summary adjudication is available both to applicants (i.e., the party alleging infringement of a patent) and respondents (i.e., the party defending an allegation of infringement of a patent).

The procedural rules relating to summary adjudication are set out in Rule 26.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). An application for summary adjudication requires an affidavit stating the grounds of the application and the facts and circumstances relied on to support those grounds. 84

The power of the court to give summary adjudication is provided by Section 31A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). The court may give summary judgment in favor of an applicant if the court is satisfied that the respondent “has no reasonable prospect of successfully defending the proceeding,” 85 and it may summarily dismiss a proceeding if it is satisfied that the applicant “has no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting the proceeding or that part of the proceeding.” 86

Section 31A(3) specifies that a defense or proceeding need not be “hopeless” or “bound to fail” for it to have “no reasonable prospect of success.” This is because the “no reasonable prospect of success” standard was adopted in Section 31A to make it easier for a party to obtain summary adjudication, in comparison with the common-law standard that previously applied, which required a proceeding or defense to be “hopeless” or “bound to fail” before summary judgment or summary dismissal could be ordered. A “reasonable prospect of success” is a “real,” rather than “fanciful,” prospect. 87

The court’s power to make orders for summary judgment or summary dismissal is discretionary. 88 The court will exercise its powers in relation to summary adjudication with caution. 89 This is particularly so where an application for summary judgment or summary dismissal requires consideration of apparently complex questions of fact, law, or mixed law and fact. 90 Where there are factual issues capable of being disputed and in dispute, the summary disposition of the proceeding would not be appropriate. 91 A proceeding will not be determined summarily unless it is clear that there is no real question to be tried.

The party bringing the application for summary determination bears the onus of persuading the court that the proceedings should be determined summarily prior to a full hearing (and prior to other court processes that may not yet have occurred, such as discovery). That onus is “heavy.” 92 If a prima facie case in support of summary determination is established, the onus shifts to the opposing party to point to some issue that makes a trial necessary. 93

A summary judgment application could be brought by a patentee on the basis that the respondent has “no reasonable prospect” of defending the allegation that its product or method infringes the patent. For example, the respondent may admit to the factual allegations of making, using or selling the relevant product or method, with the only issue needing to be determined by the court being whether that product or method infringes the patent. In these circumstances, the applicant could consider its case on infringement to be so clear that the respondent has “no reasonable prospect of successfully defending” the allegations of infringement.

By the same token, a respondent who is alleged to have infringed a patent could bring a summary dismissal application on the basis that its product or method plainly does not infringe the patent such that the applicant has “no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting the proceeding.”

A respondent could also bring a summary dismissal application on the basis that the patent is invalid. For example, if there is a publication that disclosed all of the integers of the invention claimed in the patent, but there is a dispute about the priority date of the patent and therefore a dispute about whether the publication is relevant prior art, then the respondent may decide to make an application for summary dismissal on the basis that the priority date issue can be determined without extensive evidence. 94 In such a case, determination of the priority date issue would effectively determine the issue of patent validity.

In practice, however, summary adjudication is rarely sought in patent litigation in Australia, either by applicants or by respondents. This is likely due to the fact that patent proceedings generally involve complex questions of fact and law, which are generally not appropriate for summary determination. 95

Patent litigation proceedings are typically commenced by a patentee alleging infringement, with the respondent denying infringement and cross-claiming for revocation of the patent. The court typically hears and determines infringement and invalidity simultaneously.

Once initial procedural steps, including the filing of pleadings, are completed, each party prepares evidence in accordance with a timetable set by the court. Evidence in patent cases is usually provided in the form of written and verified affidavits. Documents can be annexed or exhibited to affidavits, which are then tendered in court and admitted as evidence. Prior to trial, there will usually be one or more case management conferences and procedural steps to identify which affidavit evidence will be relied on at trial. Each party also notifies which of the opposing parties’ witnesses it will call for cross-examination.

At the trial, any affidavit evidence upon which a party intends to rely will be formally “read” by the party relying on it and admitted into evidence. A person that has given evidence in affidavit form may be required to appear for oral cross-examination by the opposing party. Cross-examination of the witness is not confined solely to matters in the witness’s affidavit: any issue relevant to the proceedings can be canvased. After cross-examination is completed, the party calling the witness has the right to reexamine the witness in relation to matters arising out of cross-examination.

Issues of patent construction and, consequently, infringement and validity are considered through the lens of a notional addressee of the patent specification – a person skilled in the art. The background and experience of the person skilled in the art will differ depending on the subject matter of the specification. Of course, ultimately, these issues are determined by the court. While the Federal Court judges who hear patent cases are generally highly experienced and often former patent counsel themselves, they do not always have technical qualifications. Consequently, in almost all patent cases, independent expert evidence is called to assist the court in placing itself in the position of the person skilled in the art.

While the Federal Court of Australia can appoint its own expert or assessor (technical assistant), these powers are rarely used, and, in the majority of cases, competing experts are engaged by the parties themselves. The purpose of expert evidence is for the court to receive the benefit of the objective and impartial assessment of an issue using the specialized knowledge of the expert. 96

Where an expert witness is retained for the purpose of preparing a report or giving evidence as to an opinion held by the expert based on their specialized knowledge, the expert is provided with the Federal Court’s Expert Evidence Practice Note (GPN-EXPT) and all relevant information so as to enable the expert to prepare an independent report. The expert’s ultimate obligation is to assist the court rather than act as an advocate for a party. The parties and their legal representatives have obligations to maintain the independence of the expert witness and must not pressure or influence the expert into conforming their views with the parties’ interests.